Learning to read can be a complex task. Reading instruction and learning are made easier by using evidence-based methods designed to help children decode printed words. You may know that there continues to be controversy about whether a “whole language” or “phonics” route is best for teaching word recognition. Research heavily supports teaching all children phonics, but also other critical areas like spoken language, including phonemic awareness and vocabulary, as well as reading fluency and reading comprehension (e.g., National Reading Panel, 2000). Take the quiz below to determine if you are a word decoding strategy guru!

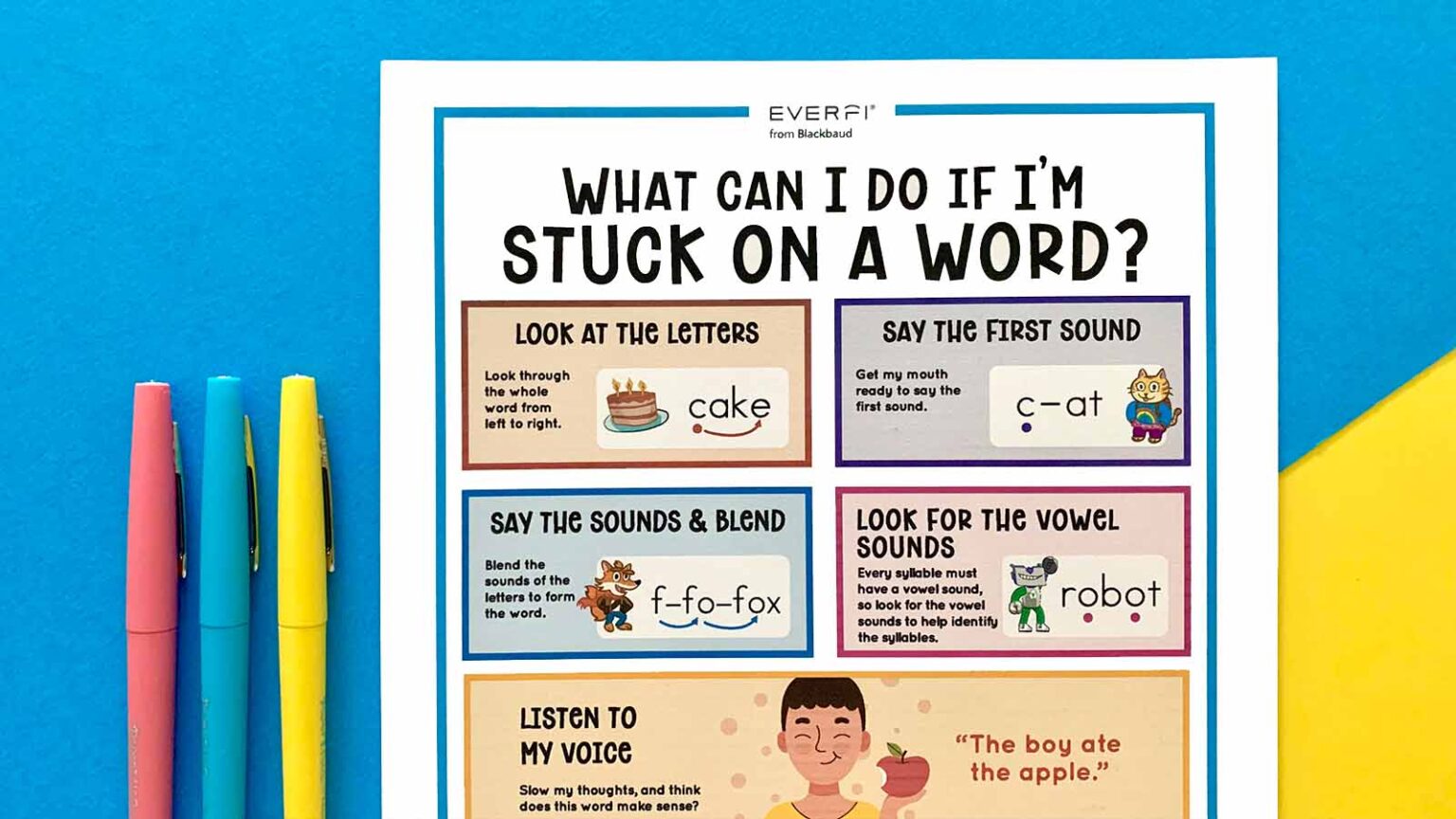

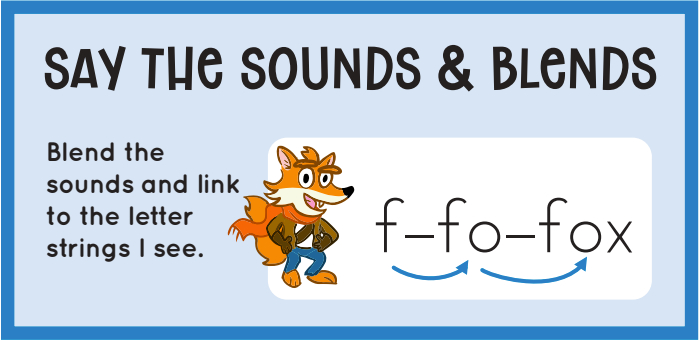

Look at the Letters

QUIZ True or False: Children should learn the association between letters (graphemes) and speech sounds (phonemes) in words.

EVIDENCE True! Researchers (Coltheart et al., 2001) have found that 80% of one-syllable English words can be decoded using a relatively small set of letter-sound association rules. Teaching children to look at the letters in words and to read from left to right sets them up for word decoding success.

TRY IT OUT

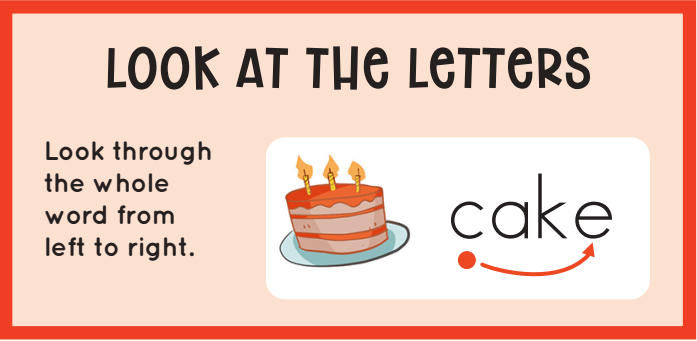

Say the First Sound

QUIZ True or False: Children should be taught to start with the first letter in a word when “sounding out” the letter-sound associations.

EVIDENCE True! As children learn to decode words that begin with a particular letter sound, it becomes easier for them to decode other words that start with that letter sound (Castles et al., 2018).

TRY IT OUT

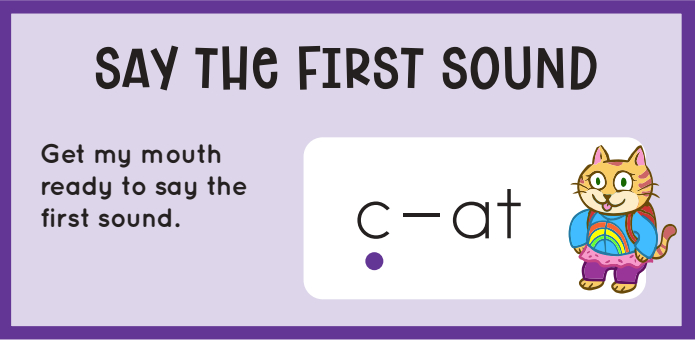

Say the Sounds and Blend

QUIZ True or False: Blending speech sounds to form spoken words helps children learn how to blend printed letters to form printed words.

EVIDENCE True! When students hear phonemes blended together, especially in a continuous manner (“sssaaattt” vs. “s” + “a”+ “t”), they can more easily decode new words when reading (Gonzalez-Frey & Ehri, 2020).

TRY IT OUT

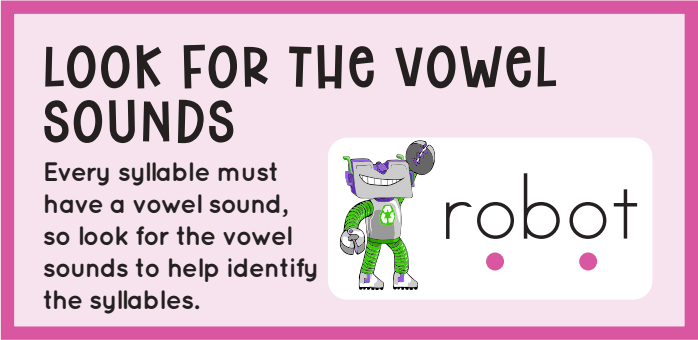

Look for the Vowel Sounds

QUIZ True or False: The number of syllables in a word is equal to the number of vowel sounds in that word.

EVIDENCE True! Knowing that vowels and their sounds mark important boundaries in a word (i.e., syllables) can help students learn to read longer, multisyllabic words (Kearns & Whaley, 2018).

TRY IT OUT

Listen to My Voice

QUIZ True or False: One way to check word reading accuracy is to self-monitor whether each word read aloud makes sense in the sentence.

EVIDENCE True! Translating printed words into their spoken forms helps children link meaning to the words, which is critical to early reading development (Nation & Cocksey, 2009).

TRY IT OUT

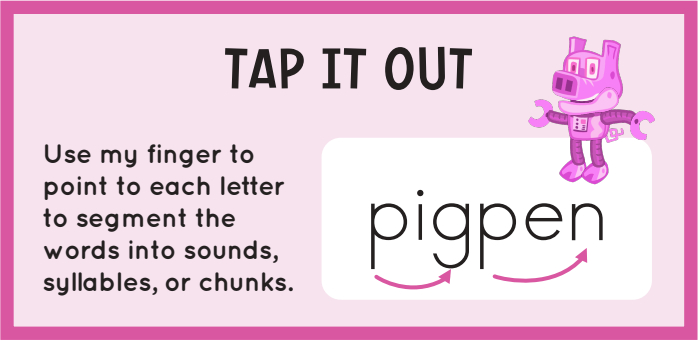

Tap it out

QUIZ True or False: Research supports word study methods which include segmenting words into sounds, syllables, and chunks.

EVIDENCE True! When children are just learning to read, it is important to help them parse out letter-sound associations and then as the words they encounter become more complex, showing them additional chunking strategies (e.g., syllables, morphological units) can be quite helpful (Bhattacharya, 2020; Ehri, 2020).

TRY IT OUT

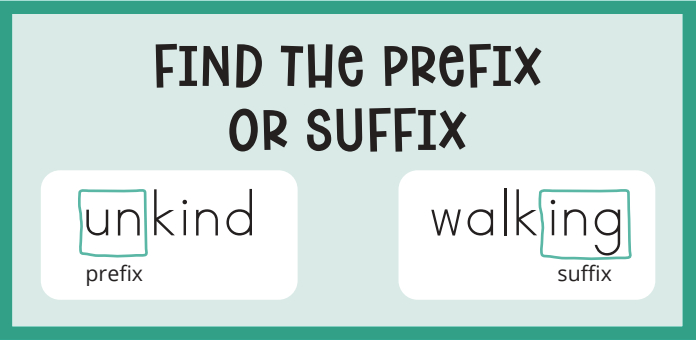

Find the Prefix or Suffix

QUIZ True or False: One component of decoding a word is analyzing its prefixes and suffixes.

EVIDENCE True! Suffixes and prefixes (known collectively as affixes) alter the meaning of words. Proficient reading happens when children can simultaneously recognize words’ spellings, how words sound when decoded, and the meaning of words (Castles et al., 2018).

TRY IT OUT

If you answered “True” to all questions, then you have notable knowledge about some of the word decoding strategies aligned with the science of reading research. Sign up here to download the free, colorful “What Can I Do If I am Stuck on a Word” poster which contains the easy to implement word decoding strategies covered above.

For free access to engaging digital early literacy games for your K-2 students, check out WORD Force, a literacy adventure.

Dr. Jaumeiko Coleman is the Vice President of Early Literacy Impact at EVERFI. In her role she enjoys collaborating with colleagues across units as well as external stakeholders on early literacy projects as a subject matter expert. Dr. Coleman’s career focus on spoken language and literacy has been infused in her work in public and private schools, public and private universities, and a not-for-profit association. She is a board member of Learning Disabilities Association of Georgia and Learning Disabilities Association of America.

References

Bhattacharya, A. (2020). Syllabic versus morphemic analyses: Teaching multisyllabic word reading to older struggling readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 63(5), 491-497. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.984

Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618772271

Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R., & Ziegler, J. (2001). DRC: A dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychological Review, 108, 204–256.

Ehri, L.C. (2020). The science of learning to read words: A case for systematic phonics instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S45-S60. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.334

Gonzales-Frey, S.M. & Ehri, L.C. (2020). Connected phonation is more effective than segmented phonation for teaching beginning readers to decode unfamiliar words. Scientific Studies of Reading, 25(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2020.1776290

Kearns, D.M. & Whaley, V.M. (2018). Helping students with dyslexia read long words: Using syllables and morphemes. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(3), 212-225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059918810010

Nation, K., & Cocksey, J. (2009). The relationship between knowing a word and reading it alud in children’s word reading development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 103(3), 296-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2009.03.004

National Reading Panel (U.S.) & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.).(2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.